(3 minute Read)

When I study confidence, I always come away with two distinct themes and one troubling thought. First, it is obvious that confidence is important, so important that even when we are tricked into having it, we perform better (Vealey & Chase, 2008). Second, it is almost always described as a feeling (Burton & Raedeke, 2008; Vealey & Chase, 2008; Zinsser, Bunker, & Williams, 2010). The part that always troubled me was why we would leave something so important up to how we feel about it. After all, the only time confidence matters is when it is tested and in most cases, we are going to be tested regardless of how we feel about it.

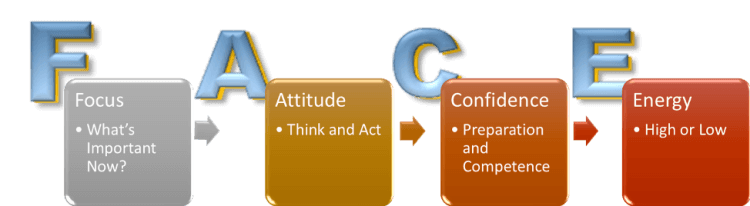

Instead, let’s consider a practical approach to ensure that we can accurately predict how well we will do despite how we feel about it. In order to do so, we should consider confidence as the result of an interaction between our preparation and competence (Vealey & Chase, 2008). Doing so makes it easier to understand and apply in any situation. The process of breaking down both preparation and competence into workable parts helps us understand how the two interact and gives us a mental checklist to use at the moment we need it most.