It is well documented that now more than ever, getting outside for exercise and fresh air has become critical for the health and well-being of all our students (Louv, 2007; SHAPE AMERICA, 2014; Steffen & Stiehl, 2010; Taylor & Kuo, 2009). This is especially the case for students who may experience varying emotional difficulties like anxiety and depression; or those who have been identified as having other challenges like attention disorders or other barriers to learning. The purpose of our paper is to offer an option for physical education and classroom teachers to provide an outside activity opportunity for students who have been identified as having Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD). The activity itself involves using an application called PuzzleWalk that can be accessed on a smartphone or other device (Lee, Frey, Min, Cothran, Bellini, Han, & Shih, 2020).

Being teachers ourselves, we do not simply look at providing Developmental Adapted Physical Education (DAPE) (Kelly, 2019) opportunities for our students as merely a necessary formality. We also view fully inclusive access to opportunities for a fulfilling, active lifestyle as a social justice issue for all our students. Equal opportunities being provided to all our students is key. We are well aware of the negative effects that technology overload is having on all our students and teachers (Mustafaoglu, Zirek, Yasaci, & Ozdincler, 2018), especially during the past year. So, we are also not coming from the standpoint of simply promoting technology use. Rather, we are embracing the notion that students who have been identified as having ASD tend to respond well to interactive technologies including human/computer interaction.

Being teachers ourselves, we do not simply look at providing Developmental Adapted Physical Education (DAPE) (Kelly, 2019) opportunities for our students as merely a necessary formality. We also view fully inclusive access to opportunities for a fulfilling, active lifestyle as a social justice issue for all our students. Equal opportunities being provided to all our students is key. We are well aware of the negative effects that technology overload is having on all our students and teachers (Mustafaoglu, Zirek, Yasaci, & Ozdincler, 2018), especially during the past year. So, we are also not coming from the standpoint of simply promoting technology use. Rather, we are embracing the notion that students who have been identified as having ASD tend to respond well to interactive technologies including human/computer interaction.

Additional aspects of our rationale are that using mobile technology as a physical activity intervention for students with ASD is their attraction to technology use due to its predictability and relatively low social requirements compared to traditional face-to-face social interactions (Kuo, Orsmond, Coster, & Cohn, 2014). Also, it is known that students with ASD possess particular strengths in visuospatial learning such as block design and image-based problem solving; this is why they are visual learners. A mobile application like PuzzleWalk allows students with ASD to be self-directed learners in their communities.

Beyond working with students with ASD, recent research in various professional fields has shown that, depending on the game type and purpose, certain video games can lead to positive effects for participants (Franceschini, Trevisan, Ronconi, Bertoni, Colmar, Double, Facoetti &, Gori, 2017; Granic, Lobel., & Engels, 2014; Zayeni, Raynaud, & Revet, 2020; Uttal, Meadow, Tipton, Hand, Alden, Warren, & Newcombe, 2013). For example, the use of electronic and video games as a therapeutic intervention has shown success in the prevention and reduction of childhood anxiety and depression (Zayeni, Raynaud, & Revet, 2020). In cognitive psychology (Keilani & Delvenne, 2020), the use of electronic and video games has been shown to help patients manage social and emotional issues as well as improve focus, multitasking, and working memory (Keilani & Delvenne, 2020). Furthermore, children with other learning disabilities, such as dyslexia, have shown improved focused visuospatial attention, phonological short-term memory and ability to interpret and blend multiple sounds, all of which can positively enhance reading skills after training with action video games (Franceschini et al., 2017).

In the field of health promotion more specifically, interest regarding the clinical use of video games has increased tremendously over the past decade. In some cases, evidence shows that there can be a positive relationship between video games and physical activity (Da Silva Júnior et al., 2021; Khamzina, Parab, An, Bullard, & Grigsby-Toussaint, 2020; Kim, Lee, Min, Paik, Frey, & Bellini,2020). These games called exergames require physical movement and increase engagement in physical activity (Oh & Yang, 2010). Similar to the very popular Pokeman Go game that is designed to get participants out and moving about (Khamzina et al., 2020), Puzzle Walk is an exergame that also promotes outside exploration and increased steps toward participants ‘steps per day goals.

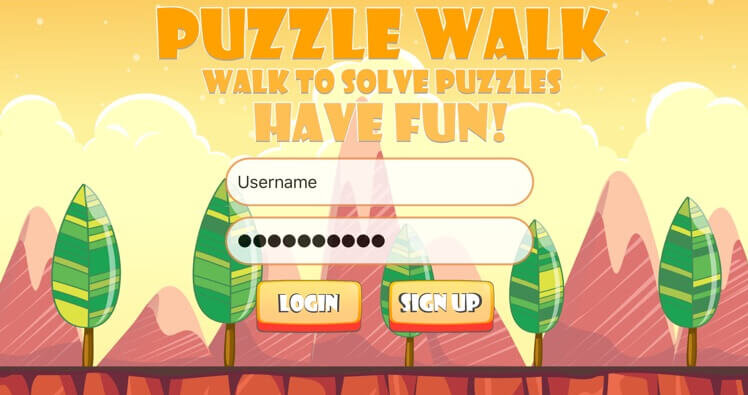

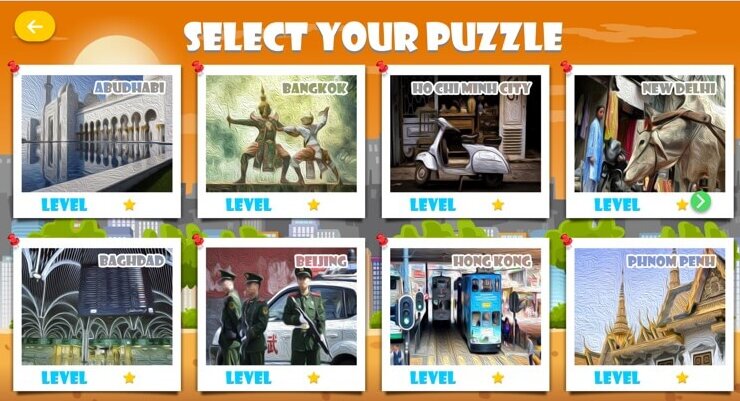

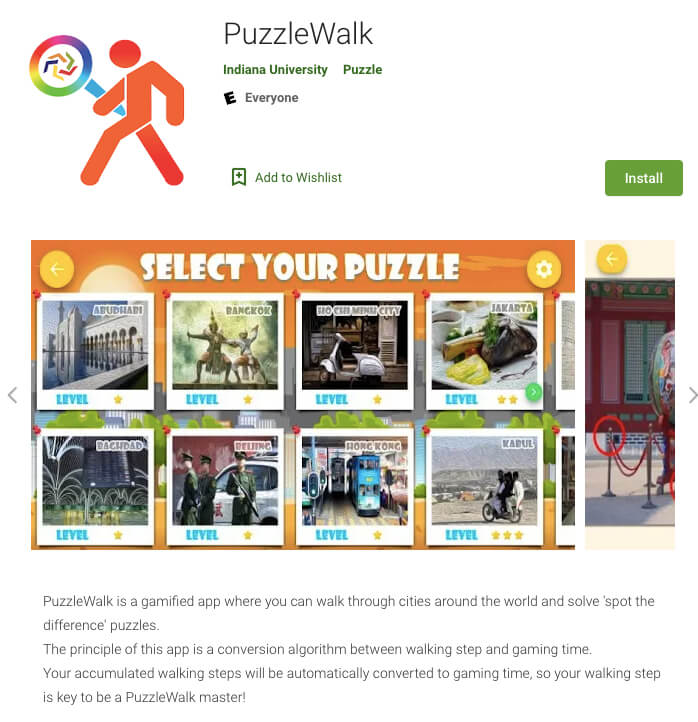

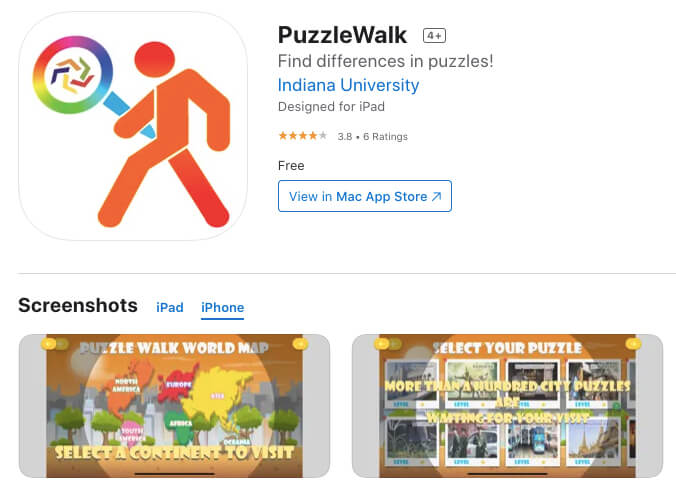

PuzzleWalk is a gamified incentive-based mobile app that leverages a conversion algorithm between daily steps and game time as a token economy (i.e., the algorithm automatically converts each step into one second of puzzle game time) (Lee et al., 2020). The app aims to increase user motivation for participating in leisure-time physical activity and reducing sedentary time by providing users with tangible monetary rewards contingent upon their step counts and puzzle scores. PuzzleWalk incorporates gamification techniques to facilitate physical activity behavior change in which ‘spot the difference’ puzzle games are used with more than 600 major city images across the world. Further, a gamified leaderboard ranks users based on their overall performance (i.e., accumulated walking steps + puzzle scores). Top 3 score-leaders receive monetary incentives on a monthly basis (e.g., $10 e-gift card) to elevate user motivation. The leaderboard resets score data at the beginning of each month to encourage consistent engagement in physical activity among users.

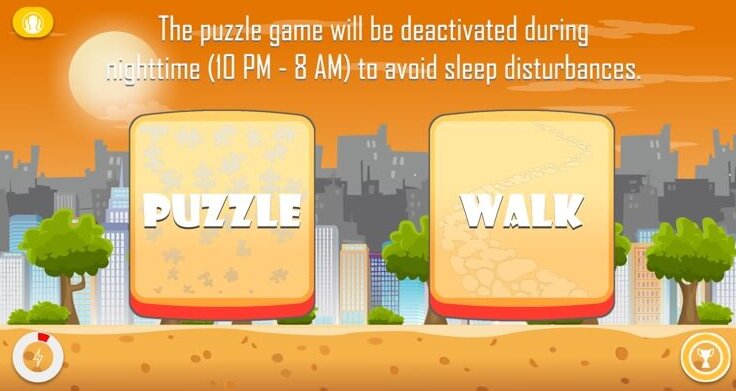

Figure 1. PuzzleWalk App on Google Play and Apple App Store

PuzzleWalk is designed to address a significant lack of preventive health interventions for individuals with high-functioning autism spectrum disorder (ASD). The app embraces the unique needs and characteristics of this population such as difficulty in social situations and strengths in visuospatial learning through technologies (Kleberg et al., 2017; Samson, Mottron, Souliéres, & Zeffiro, 2011). Given the unique strengths in people with ASD and high accessibility and affordability of mobile technology, the PuzzleWalk app can be an effective physical activity intervention tool for students with ASD in real-world settings, which can potentially increase leisure-time physical activity.

Despite the potential usability of PuzzleWalk, there are several technical limitations that teachers should be aware of. First, the step-tracking pedometer function can be an issue for iPhone users. Unlike Android phone users, iPhone users must keep the app open and running in the background of the phone to properly track steps, which can unfavorably impact a user’s continuation desire. Considering the low to moderate sensitivity/accuracy of the mobile phone’s built-in pedometer, PuzzleWalk may not detect subtle walking motion, which can, in turn, reduce user motivation. Last, some users with old operating systems (e.g., before iOS 9.0 or Android 4.4) might experience synchronization issues to convert accumulated steps to puzzle game time due to limited compatibility.

Given the social incentives and the ways in which this type of interactive technology addresses the personal attributes of participants, we recommend trying out PuzzleWalk with family members, friends, colleagues, and anyone who may be interested. Give PuzzleWalk a try and let us know what you think. Happy Exploring!

References

Da Silva Júnior, J., Biduski, D., Bellei, E. A., Becker, O., Daroit, L., Pasqualotti, A., Tourinho

Filho, H., & De Marchi, A. (2021). A Bowling Exergame to Improve Functional Capacity in Older Adults: Co-Design, Development, and Testing to Compare the Progress of Playing Alone Versus Playing With Peers. JMIR serious games, 9(1), e23423. https://doi.org/10.2196/23423

Franceschini S, Trevisan P, Ronconi L, Bertoni S, Colmar S, Double K, Facoetti A, Gori S. Action video games improve reading abilities and visual-to-auditory attentional shifting in English-speaking children with dyslexia. Sci Rep. 2017 Jul 19;7(1):5863. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-05826-8. PMID: 28725022; PMCID: PMC5517521.

Granic, I., Lobel, A., & Engels, R. C. M. E. (2014). The benefits of playing video games. American Psychologist, 69(1), 66–78. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0034857

Kelly, 2019. Adapted Physical Education National Standards: National Consortium for Physical Education for Individuals with Disabilities (3rd Ed.). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Khamzina, M, Parab, K., An, R., Bullard, T., Grigsby-Toussaint, D. (2020). Impact of Pokemon Go on Physical Activity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Preventive Medicine 58(2), 270−282.

Kim B, Lee D, Min A, Paik S, Frey G, Bellini S, et al. (2020) PuzzleWalk: A theory-driven iterative design inquiry of a mobile game for promoting physical activity in adults with autism spectrum disorder. PLoS ONE 15(9): e0237966. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0237966

Kleberg, J. L., Högström, J., Nord, M., Bölte, S., Serlachius, E., & Falck-Ytter, T. (2017). Autistic Traits and Symptoms of Social Anxiety are Differentially Related to Attention to Others’ Eyes in Social Anxiety Disorder. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 47(12), 3814–3821. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-016-2978-z

Kuo, M. H., Orsmond, G. I., Coster, W. J., & Cohn, E. S. (2014). Media use among adolescents with autism spectrum disorder. Autism: the international journal of research and practice, 18(8), 914–923. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362361313497832

Lee, D., Frey, G. C., Min, A., Kim, B., Cothran, D. J., Bellini, S., Han, K., & Shih, P. C. (2020). Usability inquiry of a gamified behavior change app for increasing physical activity and reducing sedentary behavior in adults with and without autism spectrum disorder. Health Informatics Journal, 2992–3008. https://doi.org/10.1177/1460458220952909

Louv, R. 2007. Leave No Child Inside: Testimony before the Interior and Environmental Subcommittee. Accessed Februrary1, 2021 from: https://www.govinfo.gov/content/pkg/CHRG-110hhrg35982/html/CHRG-110hhrg35982.htm

Mustafaoglu, R., Zirek, E., Yasaci, Z., & Ozdincler, A.R. (2018). The negative effects of technology usage on children’s development and health. The Turkish journal on addictions, 5(2), 13-21. Oh Y, Yang S. Defining exergames & exergaming. East Lansing, MI, USA: (2010). Available at: http://meaningfulplay.msu.edu/proceedings2010/mp2010_paper_63.pdf [Accessed July 26, 2019].

Samson, F., Mottron, L., Soulières, I., & Zeffiro, T. A. (2012). Enhanced visual functioning in autism: An ALE meta‐analysis. Human brain mapping, 33(7), 1553-1581.

Shape America, 2014. National Standards and Grade Level Outcomes for K-12 Physical Education. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Steffen, J., and Stiehl, J. 2010. Teaching Lifetime Outdoor Pursuits. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Taylor, A.F. and Kuo, F.E. 2009. “Children with Attention Deficits Concentrate Better after Walk in the Park.” Journal of Attention Disorders 12, no. 5: 402-409.

Uttal, D. H., Meadow, N. G., Tipton, E., Hand, L. L., Alden, A. R., Warren, C., & Newcombe, S. (2013). The malleability of spatial skills: A meta-analysis of training studies. Psychological Bulletin, 139, 352–402. doi:10.1037/a0028446

Zayeni, D., Raynaud, J. P., & Revet, A. (2020). Therapeutic and Preventive Use of Video Gamesin Child and Adolescent Psychiatry: A Systematic Review. Frontiers in psychiatry, 11, 36. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00036

Closing the academic and life-skills gap can be achieved by closing the opportunity gap. Here is another opportunity to engage in a fun-filled activity that is interactive and easy to access for challenged individuals. KUDOS to the authors of this article!