(This four-part article describes the legacy of the Snow Valley Basketball School on coach development and the game of basketball)

————

If the Coach is Learning the Athletes are Improving

Charlie Sands fled to a corner of the gym, trapped as the pressure of over 300 young athletes pushed against him. The hall of fame coach from West Los Angeles College had ignited the group during a final warm-up session. His spirited approach was creating a frenzied atmosphere. A fitness fanatic, Coach Sands became a legend at Snow Valley for his ability to motivate and inspire young people to come together as a group. This particular warm-up session was an accumulation of all the activities he’d led during the past week.

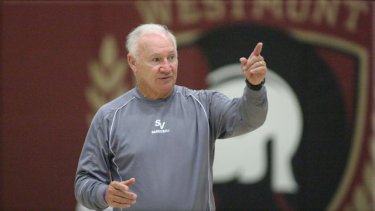

Charlie Sands. Photo credit: US Sports Camps

“You would not believe how electric the atmosphere in the gym was,” recalled Clete Adelman, “He (Charlie) would be out in front of 300 kids and anything he tell them to do, he would do. I mean jump stops, jumping in the air, diving on the floor… everything they did the whole week.” As Adelman reflects, “The kids are going crazy. Charlie is out there doing all this stuff. He is sweating like a sinner in church. I mean he is dripping wet. It was so emotional. So powerful.”

Charlie Sand’s relentless energy coupled with his ability to teach, led Herb Livsey to hire him in 1974. Sands would spend 42 years at Snow Valley eventually serving as part-owner. He would become a key partner in promoting Livsey’s vision to run a top instructional basketball camp, along the way helping coaches become better teachers.

The Snow Valley Way

The eyes of the young athlete focus intently on the coach: The lead clinician’s authority established. Now in the spotlight, with their teaching approach exposed for critical review, the lead clinician goes to work. Campers listen as the skill is introduced. Basket coaches shift closer to understand their role. Some are taking notes. The lead, presents a detailed explanation of the skill, explains the drill, and then disperses the group to a series of baskets. The basket coaches run the drill and provide feedback as the athletes practice the skill. The campers, organized by age groups are accustomed to this teaching style. This is the Snow Valley Way.

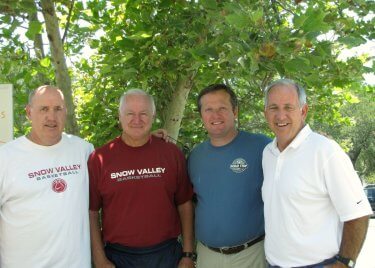

Carlson, Livsey, Sands, Middleton. Photo credit: Steve Middleton

Campers like the Snow Valley Way because they see their skills improve. Coaches like it too because they are learning new ways to teach skills. Wayne Carlson observed hundreds of instructional clinics over the years at Snow Valley. “While you watched the coaches teach you sat there and took notes. Then you would go out there and do the drills or the clinic, come back and write down more notes,” shared Wayne. “So not only were you taking notes on things you wanted to use in your own program, you would see the drill and then get to practice teaching it.”

Livsey structured the clinics to teach skill progression. Instructional clinics were repeated throughout the day during the entire week of camp. To lead an instructional clinic was an honor. A moment to shine. An opportunity to rise to the challenge. Livsey would carefully select and assign coaches to be lead clinicians and determine which coaches might work best as a basket coach for that particular clinic. A coach working the camp may serve as a basket coach for one clinic and a lead clinician in another session. It created a setting for coaches to practice and reflect on their craft.

Becoming a Better Coach

To work at Snow Valley was a commitment to becoming a better coach. Beyond the long 16 plus hour days, a coach was immersed in a culture where the development of the coach was almost as important as teaching basketball fundamentals. Livsey wanted Snow Valley to be a learning environment for coaches. Often, Livsey would assign an established coach to a dorm room with an up-and-coming coach. He knew that the younger coach’s enthusiasm would generate discussion and allow the veteran coach to share his wisdom. It was an exchange that benefited both parties.

Adelman, Sands, Middleton, Carlson. Photo credit: Steve Middleton

“The first year I was at Snow Valley I was a fired up young guy in my early 30’s and I roomed with Al Burger,” Adelman recalls, fondly reflecting on the memory. “Because I was rooming with him, I followed him around like a puppy dog.”

Al Burger was a long-time high school coach and well-known among the Snow Valley coaching fraternity. An inquisitive coach always seeking new coaching tips, Burger left an impression on the young Adelman. “He had this 31-page laminated notebook of people that taught the passing game. He would go around and ask people the same questions about the passing game,” recalls Adelman. “It started hitting me that here was a guy that could teach the game and he could still learn from others if they had a phrase, a term, or a drill that was going to help him.” Adelman’s experience in learning to coach was echoed by many camp coaches over the years.

Sixteen-year camp veteran Pete Gaskill, a Director and Lead Instructor for Genesis’ Elevate Basketball Academy in Kansas City, remembers being in awe his first year, “I’m a 22-year-old kid – thinking what am I doing here? My experience was significant in terms of gaining a better understanding of the game. But most importantly how to communicate it and how to teach it,” said Gaskill. “Everything I do seems to come back to Snow Valley.”

Wayne Carlson passionately looks back on the experience, describing the impact it had on his teaching in the classroom. “You take those teaching lessons not only from the basketball court, but into your history class,” says Carlson. “You’d watch them (coaches) and how they taught, how they worked with a group of kids, how they understood if learning was taking place and if learning was not taking place. Then how they would re-teach it.”

Due to the camp’s organization structure and because coaches spent so much time together, coaches began to see Snow Valley as a week-long coaching clinic. In his role as camp administrator, Steve Middleton began to notice the reason coaches worked Snow Valley, “It was not because we paid them a lot of money,” Middleton recalls, “It was because they could come for a week and immerse themselves with people who had a passion for the game. You could sit and hammer out X’s and O’s with some of the best coaching minds in the business.”

The unstructured clinics began in the dormitory’s common area: Often a bleak space adorned with a few well-worn chairs and possibly a table or two. If lucky, coaches would salvage an old blackboard from somewhere in the building. But what the setting lacked in atmosphere, did not diminish the enthusiasm among the coaches. Ideas flowed freely. Questions flourished.

Livsey remembers coming upon coaches conversing about games after a long day of camp. Coaches had a lot to share. Some like Mark Grabow could hold a room. Grabow, a long-time player development specialist, spent 23 years as Director of Athletic Development with the Golden State Warriors. His book, Mark Grabow’s On-Court 100, features over 100 drills to develop basketball skills and conditioning. “He held clinics in the living room of the coaches’ dorm,” remembers Livsey. “He would start at 8:00 and go into the wee hours of the morning, as long as the coaches wanted to stay.” Coach Grabow’s sessions were one of many informal clinics that left a mark on Snow Valley and Livsey, eventually leading to advancements in the teaching of basketball skills.

The manner in which the Snow Valley Basketball School was structured, from the instructional clinics to informal conversations, provided a framework for coaches to develop. For the coach it was more than a matter of seizing the opportunity to learn; Livsey established a higher standard – pushing coaches to be better.

Tim Grgurich instructing the defense. Photo credit: Steve Middleton

“Herb Alert”

Livsey monitored all aspects of the camp, especially when it came to the quality of the teaching. He never wanted to sacrifice the teaching of basketball fundamentals. Livsey frequently observed the activity of the coaches, constantly evaluating their passion, willingness to learn, and ability to teach. Not every coach would make it through the week. Occasionally some would quit or he would send them packing. If you were not there to work, learn, and teach the game, Snow Valley was not the place for you and you did not survive.

When Snow Valley moved to Westmont College in 1971, Livsey finally had his indoor facility. But he never intended to abandon outdoor instruction. In order to accommodate the camp during the summer months, Westmont College Plant and Facilities personnel would convert the parking lots into basketball courts. As the number of campers grew, much of the camp remained outdoors on many of the parking lots scattered across campus.

It was during the instructional clinics, where Livsey and fellow camp directors would roam the different locations and observe coaches teaching. Steve Middleton remembers the first year he moved into an administrative role with the camp, “I opened up (the office), listened to a few voicemails and then was sitting in the office. He (Herb) walks in and says, ‘What are you doing? – get out there and watch some guys teach – take notes – see what they are doing – let them know what you think they did well – learn something,’” recalls Steve. “He gave coaches flexibility – but he wanted to make sure the kids were learning.”

Because Livsey’s drive and intensity were so strong, coaches were often intimidated by his presence. According to camp legend, Coach Livsey could intimidate with his stare. “If a coach was working a basket, he would walk up, stand there, and just stare. It scared the hell out of guys because they did not know what to think,” remembers Adelman. So much so, that they coined the term, “Herb Alert.” After a couple long days at camp a coach might struggle to resist the urge to find a shade tree or sit in a chair while the lead clinician was talking. A coach would say, “Herb alert” if they saw Livsey walking towards the courts they were working at. Once they knew Livsey was near they would straighten up.

Camp stories recall that Herb hid in the bushes to evaluate coaches. No video evidence can confirm this rumor, but coaches argue it’s true. In fairness, whether Livsey hid in the bushes or not, his intentions were pure. He was likely not trying to catch a coach slacking but ensuring that coaches teaching the clinics were doing it the way he wanted it done. Livsey’s intensity in running the camp was unparalleled. Snow Valley meant so much to him and it had to be run a certain way. Coaches working the camp understood this, but this did not mean they necessarily felt comfortable. Thus, the “Herb Alert” phrase became not only a warning, but a shared experience among the coaches – strengthening their bond and becoming a part of the Snow Valley experience.

Photo credit: MD Janiska (https://www.instagram.com/md_janiska/)

The Coach’s Experience

Aaron Christian by all measures was a veteran on the summer basketball camp circuit. By the time he worked a Snow Valley camp in the summer of 2001, he had worked hundreds of basketball camps all over the country. But he had heard stories about Snow Valley – he knew it was different. “I remember being scared…(thinking) I can’t mess up, I can’t mess up,” recalled Christian, laughing at the memory. “Herb played a big role in that. Him and Charlie Sands. They did not put up with anything. You didn’t want to upset them, and you didn’t want to let them down.”

Commitment, hard work, and confidence were all likely traits shared among the coaches, since most of them were either recruited to work the camp or recommended by a former Snow Valley coach. Nonetheless, these qualities did not calm Aaron’s nerves that first week he worked camp. He simply wanted to do a good job and fit in. Early in the week Livsey approached him. Aaron still remembers the conversation going something like this:

“I need you to do something for me today, Aaron,” pipes Herb in a very direct and blunt manner.

Aaron responded, “Sure, Herb, what do you need?”

Livsey continues, “I need you to teach one of the shooting sessions this afternoon. One of the lead instructors had a home emergency and we need you to do it.”

“Sure,” Aaron said, completely caught off guard.

“Immediately I am going oh crap – oh crap – why are you picking me,” recalls Aaron? “But I remember at lunch time going into my room and mapping this whole thing out. How am I going to teach this? I don’t want to screw this up.” After the clinic was over, Aaron reminisces about his interaction with Livsey.

“Livsey says to me, ‘Nice job!’ I thank him with a bit of hesitancy,” says Aaron. “He was slightly taken aback and comments, ‘You seem relieved?’ I followed with, well that was kind of daunting to let the new guy do that. He just said, ‘I wasn’t worried.’”

As a young coach in the 1970’s, Wayne Carlson still remembers officiating a game at midnight. One of the coach’s responsibilities at Snow Valley was to officiate the evening game if they were not coaching. The game was between juniors and seniors, otherwise known as the Western Division. It also featured Don Meyer and Rick Majerus, two basketball coaches that would go on to national fame and make a lasting impact on the sport.

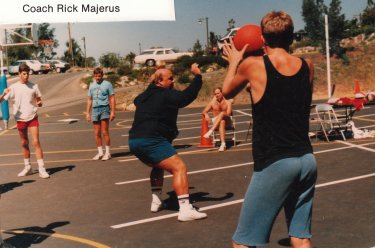

Rick Majerus Photo credit: Steve Middleton

Carlson still seemed in awe when sharing the moment, “Here I am 25 years old and I am reffing a midnight game at Westmont College. I’ve got Rick Majerus coaching one team and Don Meyer coaching the other team, and these guys are chewing my butt. Make this call! Make that call! I was young at the time and I could run up and down the floor. I was busting my butt to do a good job!”

The camp wore coaches out. Not just physically from too many hours standing on the unforgiving surface of a concrete slab or hard maple floor, but mentally – the constant pressure to perform at a high level. To complete a week of camp was an accomplishment. A moment celebrated among the staff.

Learning to become a better teacher of the game, instilled confidence in the coaches working Snow Valley. The Snow Valley coaching experience validated what they knew, exposed them to new methods, and challenged them to reflect on what it meant to be a coach. When a coach evaluated their experience after working a camp, most of the reflection came from self-assessment – internal feedback. To truly know you had done a good job came later, well after the week had ended when you were asked to come back the following year.

To Be Asked Back…

During each day of camp, in addition to the instructional clinics coaches had one practice with their team. This was an opportunity to implement skills the campers had been learning into team concepts. During the practice session, coaches connected with their players and gave detailed feedback. To ensure each boy or girl who attended the camp received similar feedback, Livsey implemented a report card. Each coach was required to deliver a formal evaluation of the young player’s skills by the end of camp. Over the years the report card evolved and developed to match the changes and improvements in how skills were being taught.

While participants in the camp received prescribed feedback on their performance, there was no formal assessment of coaches. At the end of camp, Livsey would sit down with the camp directors and they would evaluate the staff. Which coaches did a good job? Who should they invite back? To coach at Snow Valley you needed to be able to demonstrate three attributes: One, energy stemming from a passion for the game; two, a willingness to learn by improving your skills as a teacher; and three, the ability to teach. A coach demonstrating the three characteristics was likely asked back the following year. The skill to teach was paramount to the success of the camp, but Herb understood that coaches were still learning. Thus, Livsey knew he needed to have a balance of experienced and young coaches. He believed that each coach brought a unique skill set and personal experiences to the camp, and that you could learn something from everyone.

Not unexpectedly, coaches bonded after working closely together over several days. But there was also something special about working a Snow Valley camp that united coaches. Was it the long hours together? The learning environment created by the instructional clinics? Or did it go beyond that? How the game of basketball was being taught was changing and more than ever, making connections with other coaches mattered.

In the next article (Part III) – A Game is Changed. How Snow Valley impacted the way the game of basketball was taught and changed the coaching profession. Read Part I here and Part III here

Pete I am really enjoying your articles on Snow Valley. As a 13 year veteran of Snow Valley and a coach who started there when he was 23, everything said here mirrors my experiences. I still remember as a young guy being asked 6 years in a row to coach all three weeks, back to back to back, it was an exhausting experience, and as dead physically as I felt at the end of those three weeks, in a basketball sense of was fresh and invigorated. Thanks for writing this.

Thank you for sharing the impact of SV on you and for reading the series!