Most teachers I know are always looking for ways to improve their practice so they can better serve their students. We strive to develop more effective assessments, more engaging lessons, better classroom management techniques, stronger interpersonal relationships, the list goes on endlessly.

When I reflect on my own teaching and try to answer the question “How can I better serve my students?” I find myself challenged with a related question, “Where should I strive to have most impact?” Should it be in the gym and on the fields, or on the streets and in the yards?

I have always been a firm believer that a strong physical education program (among many things) serves as the foundation for a healthy life, but wonder whether my teaching reflects this. It is easy to say that PE can provide the foundation for healthy living, it is even cliché to a degree, but I still wonder, “Am I truly teaching all of my students how to do it?”

Many questions come to mind. Am I breaking down the barriers that are preventing them from being active when they aren’t with me? Are they understanding why they are being asked to meet my expectations and why it is so important, or am I simply dangling carrots during class to get them to meet my standards, my criteria and my expectations of what constitutes a good grade in PE? Am I losing the true meaning of play? Am I appropriately balancing the importance of learning and assessment with the importance of moving and playing?

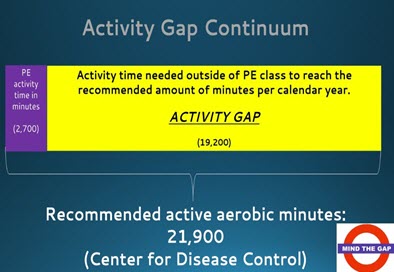

Looking at the activity gap is one of the many ways I use to address my questions. Simply put, the activity gap is the amount of recommended cardiovascular activity children need in a calendar year, compared to the amount of time they get in physical education on average. Accepting the 60 minutes a day, seven days a week recommendation, simple math reveals that children need at least 21,900 minutes of activity a year.

Students in my physical education classes get about 2,700 minutes of physical activity annually (40 minute classes, minus 10 minutes to change equals 30 minutes of possible activity time, multiplied by 90 days of class). That leaves 19,200 minutes of moderate to vigorous activity that I’d like my students to complete on their own.

Although some students make up a chunk of that time through sports and other activities, many don’t. Standing in the outfield for long stretches of a practice or game hardly counts. Many students lack the confidence to do what it takes to get moving. They dislike traditional sports and games, don’t know where to go or have nowhere to go, and don’t have anyone to go with them.

Although it’s unfair to hold physical educators solely responsible for what our students do when they are not with us, I do feel that it should be our self imposed responsibility to provide our students with the tools necessary to close this gap, whatever those tools may be. In the remainder of this essay, I’ll describe some of the strategies I’ve found effective in closing this activity gap.

Re-evaluate Assessment

The way we choose to assess and grade our students has an impact on how they feel about activity in and out of class. Sometimes, no matter how long units are they don’t provide students enough time to become skillful. This isn’t necessarily a reflection on their lack of effort or the teachers’ abilities. But unfortunately students who continuously perform poorly on assessments are much less likely to develop the desire to go and perform those same activities on their own time.

Because assessing our students on their physical development is an important part of our curriculum, how do we fairly assess them? One technique I’ve found successful is video analysis self-assessment that illustrates the internalization of a skill rather than its execution. For example, to assess a student’s ability to throw a ball, I often use the Hudl Technique app (formerly called Ubersense). I record my students executing the skill using a school iPad.

Afterwards, the student and I review the video and I ask them two questions. What do you want to keep, and what do you want to change? The first question essentially asks them to tell me what they feel they did correctly. The second tells me where they would like to see improvement if they had more time to practice. The student goes through the various parts of the skill taught to them, telling me what they want to keep, what they want to change and what those changes should look like.

For example, if a student did not step to their target when throwing, they may say something like, “I want to change my footwork. I stepped to the side with my lead leg instead of stepping to my target.” When the assessment is complete, the video is deleted. This type of assessment lets me know that the student has learned what the skill is supposed to look like. They understand it but just need more time to master it. Actively assessing students based on what they know in regards to movement is meaningful and does not turn students off activity because they are struggling with some of the skills.

Instill a Growth Mindset

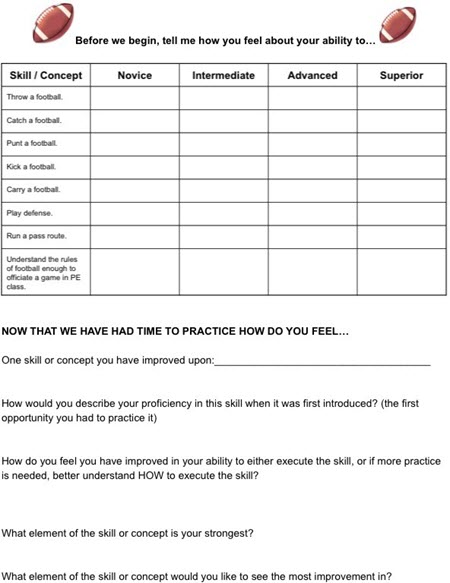

Every time we teach a lesson there are students that have already made up their mind regarding their ability to complete a given task. If they don’t think that they are able to participate in an activity with any semblance of success, they are much less likely to choose to partake in that activity on their own time. Part of our job is to try and change the perception that they can’t and to get them to believe that they can. The following form serves a major purpose in my classes: It shows students that with effective effort growth can occur.

The table serves as a pre-assessment for my students. Before anything is taught, the students’ rate how they feel about their abilities to perform a variety of skills related to the upcoming unit. Towards the end of the unit, students get their sheets back and complete the bottom portion that asks them to pick one skill that they have improved upon and explore it further.

During class discussions, students also share specific examples as to why they feel the growth occurred. More often than not, students will be able to see growth in at least one area of what was taught. Through reflections such as this I can help my students to identify improvement and take ownership of this achievement. It is very rare that students will not be able to see improvement in at least one area of instruction during the course of a unit However, if that occurs teachers should review their instructional strategies, lesson content and student motivation.

Create Flexible Learning Environments

Peter Gray in his TEDx talk entitled “The Decline of Play” defines play as being “self-controlled and self-directed.” Sadly, the majority of the opportunities that our students have to move in their daily lives are too structured and over-organized. Kids today are on teams, go on play dates, and participate in many PE classes where they often times learn scripted rules and scripted strategies. Although, these rules and strategies may be important to a student’s well-rounded education, ,the over-structured world that our students have been born into has stripped them of their ability to exercise their creativity and really play.

For example, some time ago I realized there were students in my classes, who for various reasons did not enjoy playing the sport of volleyball. Forcing them to play the game solely following traditional rules only increased their frustration and disinterest in the game. However, when I challenged my students to create their own modified, more enjoyable version of volleyball they developed an activity they wanted to play and so helped to close the activity gap.

In my volleyball unit I like to implement a three-court system where appropriate. Any students choosing to play on court one play the game in the traditional way, utilizing all of the rules, tactics and strategies learned in class. Students choosing to play on court two, play the game according to a set of pre-determined modifications designed to extend volleys and keep the game moving. Students opting to participate on court three have the ability to play a game using a volleyball and a volleyball net. Essentially the students on court three are free to make the game up as they go along.

If you allow students this flexible option it is important to set clear class standards for behavior, respect and cooperation. Often times I observe students moving from one court to another until they find their home. Eventually they settle in and when that happens, participation, enjoyment and success all increase. No matter which court the students choose to play on I still hold them responsible for the learning that day, but the play time is theirs to explore.

One of my favorite student quotes came three years ago on the first day of school. An eighth grader saw me in the hallway and yelled “Hey, Mr. Rizzuto!” I walked over to her and she asked me if I remembered that “silly” volleyball game they made up the previous year in my class. I told her I did to which she said “we played it all summer!” That summer, the activity gap shrank!

After School Programs

After School Programs

There are many plausible explanations why kids do not play the way or as much as they used to. Socio-economic differences, lack of motivation due to excessive organization and adult control, and parental perceptions of neighborhood danger are just some of commonly cited reasons. Common to all of these is the lack of availability for children to safely enjoy play.

At a recent New York State AHPERD conference, I described my vision of an after school program that is student organized, student driven, student directed, and obviously student centered. I called the program the GAASP program, which stands for Growing Activity Among Student Populations, with a small play on the word “gasp,” as in, gasping for air.

I’m happy to say that I am now piloting an after school club at my school that includes a GASP program. The students have visions of supervised open gym time where they are in total control of the activities, and more time in the weight room with a teacher on hand to supervise and assist students who need help. Nature hikes, fun runs, basketball tournaments and “Minute to Win It” nights are all on the future docket.

After the program is up and running for a little while, we are going to set activity goals for each individual and the school as a whole and see how far we can go to closing the activity gap. I encourage you to take the time to brainstorm a similar program that will meet the activity needs of your students, and when you do, contact me and let’s see if we can all work to close the activity gap together!